A Variant of the Codical T501 HA’ Logogram

Clio Reichart and Uguku Usdi

The In Lak’ech Study Group

California Substance Abuse Treatment Facility/State Prison

Corcoran, California

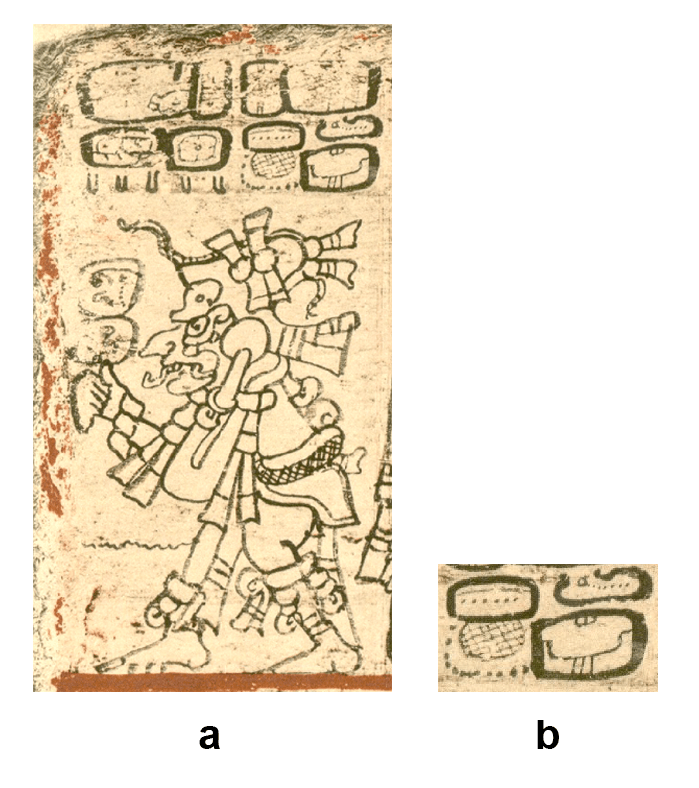

On page D33a of the Dresden Codex, at B2, there occurs an augural collocation that is composed of what seems to be a variant of the T162 superfix under which appears, on the left, an unidentified glyph and, on the right, the T506 WAJ logogram (Figure 1). It is the unidentified glyph on the lower left that is the focus of this inquiry, composed of a cross-hatched oval partially surrounded by an arc of dots.

Linda Schele and Nikolai Grube, in their commentary on the Dresden Codex (compiled for the XXIst Maya Hieroglyphic Forum at the University of Texas at Austin [1997:216]), read the glyph as k’u and translate it as “holy,” while Erik Velásquez García, in his commentary on the codex that was published in two “Special Editions” of Arqueología Mexicana (2017:61), reads the glyph as k’u[’]and translates it as “nest” (translated from the Spanish by the authors). In neither case is it clear whether the authors view the glyph as a syllabogram (k’u) or a logogram (K’UH), but presumably these readings are based on the glyph’s superficial similarity to T604, the “eggs-in-a-nest” glyph (Thompson 1962:453; Macri and Looper’s 22B [2003:280]) (Figure 2).

We propose, however, that the glyph in question (on D33a at B2, Figure 1) is distinguishable from T604 and is, instead, a unique variant of the T501 logogram read as HA’. We further posit that such an assertion is supported graphically and contextually.

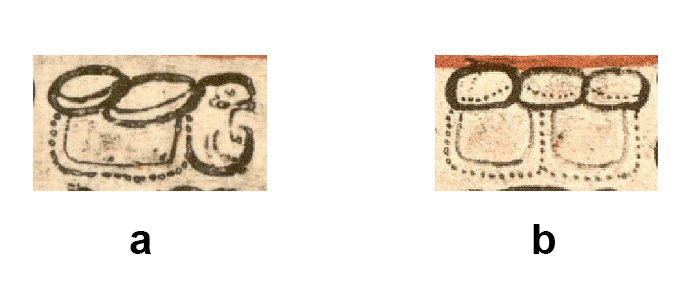

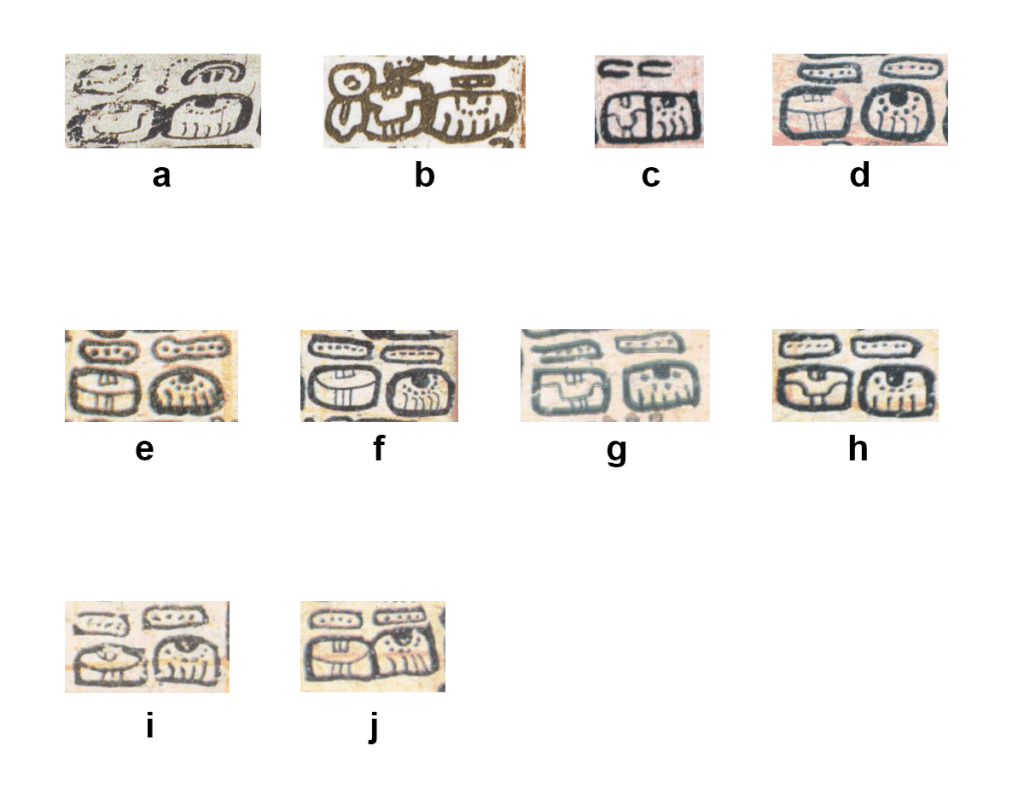

The Classic T604 graphically is said to represent eggs in a nest (Macri and Looper 2003:280), depicted as two eggs under which is a curved rectangular element composed of cross-hatching surrounded by a line and a semi-circular arc of dots (Figure 2). In the Postclassic codices, however, the same glyph, representing both the logogram K’UH and the syllabogram k’u, is depicted without cross-hatching in almost every instance, although the other elements are typically present, the two eggs under which appear a rectangular or curved line and a semi-circular arc of dots (Figure 3).

In the Dresden Codex, codical T604 appears but twice, on D13c at C1 (k’u-chi, k’uuch, “vulture” [Kettenen and Helmke 2020:110]) and on D16c at C1 (k’u-k’u, k’uk’, “quetzal” [Ibid.]), both of which appear sans cross-hatching (Figure 3). Regarding these examples, Thompson commented on the absence of the cross-hatching: “In the codices the glyph without hachure seems to be that of the quetzal; with Glyph 219 affixed the glyph may represent some species of vulture (identification proposed some sixty years ago by Cyrus Thomas)” (Thompson 1962:228; cited in Macri and Looper 2003:280 and Macri and Vail 2009:219, emphasis added).

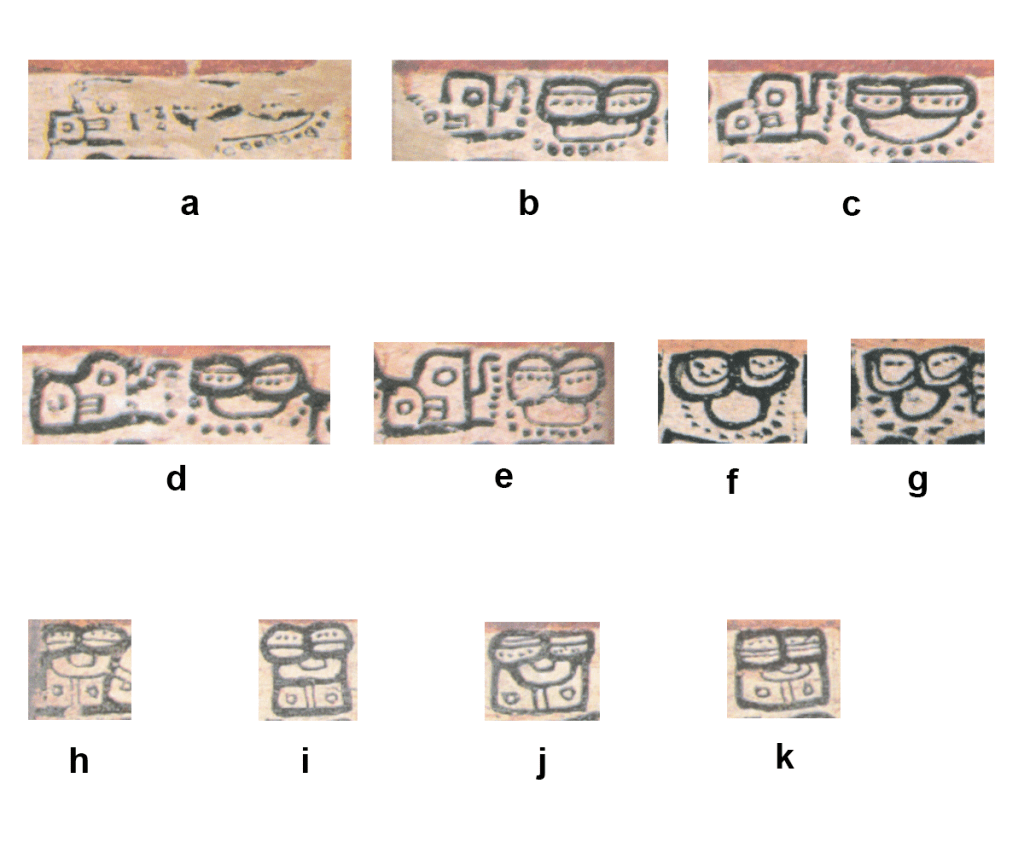

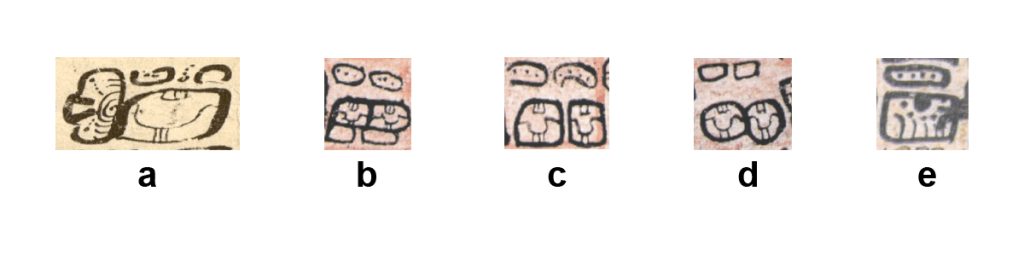

In the Madrid Codex, the k’u syllabogram or K’UH logogram is almost universally depicted like the examples found in the Dresden Codex, i.e., two eggs, a rectangular or curved line, and in most cases a semi-circular arc of dots, as in the following examples: Madrid page 40a at D1 (k’u-chi, k’uuch, “vulture” [Kettunen and Helmke 2020:110]) and Madrid page 70a at D2 (k’u–yu, k’uy, “owl” [Ibid.:108]) (Figures 4a-d). The authors understand that the Yucatec Maya word for owl is not glottalized, but as the scene below the text depicts God L with an owl, the word for owl is presumed to be intended and thus k’uy may represent a misspelling, a glottalized form of kuy, “owl” (Ibid:108).

There is another apparent misspelling of “owl” on Madrid 94c where k’u–yu (read from bottom to top as is the collocation next to it, mu–ti, mut, “bird/omen”) exhibits the only codical version of T604 with cross-hatching (or the spelling could be an intentional spelling of yuk’, “universal thing known to all” [Barrera Vasquez et al. 1980:981]) (Figure 4e, f).

As comparisons, Dresden Codex page D10a at B2 shows an owl spelled ku–yu, kuy at B2, and another owl, read in reverse order i.e., right to left, ku–yu, on D7 at C2 (Figure 4g-j).

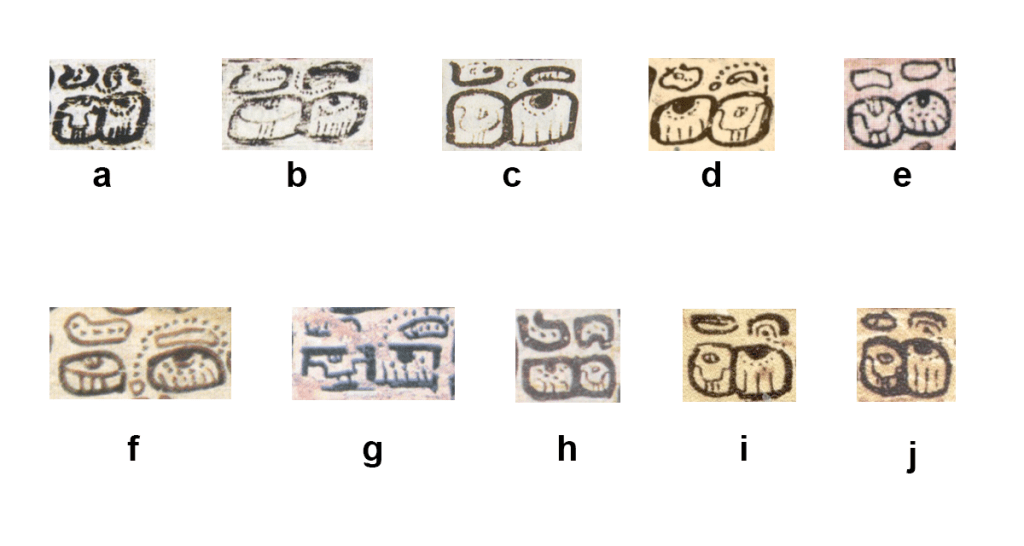

More examples of codical k’u or K’UH, all without cross-hatching, are found on Madrid page 80b at F1 and 81b at B1, D1, F1, and H1, in each case used in the phrase chu-ni K’UH, chun k’uh, “to conjure [the] deity” [Kettunen and Helmke:89, 110]) (Figure 5a-e); on Madrid page 96b at E1 and G1 (context unknown) (Figure 5f, g); and on Madrid page 104c at A1, C1, D1, and F1 (k’u-la, k’u’ul, “godly, divine” [Ibid.:110]) (Figure 5h-k). In these latter four cases, Figure 5h-k, the la syllabogram (inverted ajaw glyph) covers the curved line and arc of dots normally seen below the eggs.

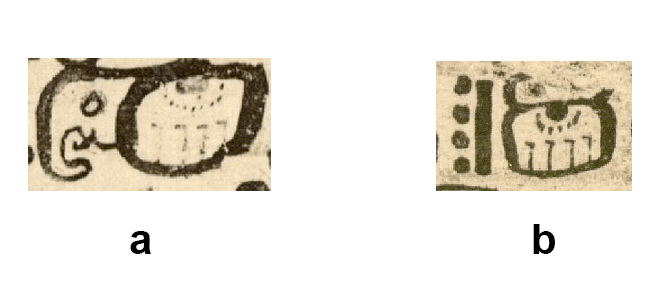

In the Paris Codex there exists but one readable example of T604, page 2b at C11 (Figure 6). Though its context is unknown, it exhibits all the hallmarks of the codical k’u or K’UH (two eggs under which appear, sans cross-hatching, a rectangular line and a semi-circular arc of dots).

Returning to the question at hand, the collocation on Dresden page 33a at B2 (Figure 1), which Schele and Grube and Velásquez García read as k’u andk’u’, respectively, do not exhibit the hallmarks of codical T604, K’UH/k’u: there are no dual eggs and there is cross-hatching where codical K’UH/k’u does not have cross-hatching (in the one exception that does have cross-hatching, there is no curved line between the cross-hatching and the curved line of dots).

Presumably Velasquez Garcia (2017:61) views the rectangular element superfixed to the cross-hatched glyph as representing the eggs of the K’UH/k’u glyph. If such were the case, it would constitute the only occurrence in the whole of the Maya codices in which the dual eggs—a key element in identifying T604—are depicted as a single egg.

As alluded to above, it is our contention that the rectangular element above the cross-hatched element is the left part of the two-part glyph known as T162, a widely attested superfix to the augural WAJ HA’, one of the most ubiquitous auguries encountered throughout the Maya codices, a collocation that may be transcribed T162:506.501 using Thompson’s (1962) catalog numbers, or 32P: XH4.XE2, using Macri and Vail’s codical nomenclature (2009:238, 133, 144).

Schele and Grube (1997:84, 91) read the T162 superfix as k’a, “abundance” a “surfeit.” Velásquez García (2016:16) seems to offer a reading of o’och’ for the entire collocation with a meaning of “food(?)” (translated from the Spanish by authors). In their codical catalog Macri and Vail (2009:238) assign no specific reading to the glyph (designated as 32P), but state that Victoria Bricker offered, via personal communication, the reading of o’och, “food, sustenance.”

Interestingly, Macri and Vail (Ibid.) note that MacLeod (1991) and Schele (1997:84) both classify the T162 glyph as the codical variant of the Classic T128 glyph, which today has a seemingly universally agreed upon reading of TI’ (Stuart 2005:63; Johnson 2013:315; Kettunen and Helmke 2020:117). Based on the equality between the Classic T128 glyph and the Postclassic codical T162 glyph, we offer a reading of CHI’ (or perhaps CHII’) for the T162 glyph, which would be the Yucatec Maya variant of TI’.

Regarding the WAJ and HA’ logograms, there is almost universal agreement that the T506 and T501 logograms are read as WAJ and HA’ respectively. Taken together with the T162 superfix, the combined collocations of T162:T506.T501 or T162:T501.T506 occur 146 times across the Maya codices (the following counts include only those occurrences in which all three elements are present and readable, omitting several instances in the Madrid Codex in which WAJ HA’ and HA’ WAJ appear without a T162 superfix).

In the Dresden Codex T162 WAJ HA’ appears 25 times compared to 24 times for T162 HA’ WAJ, which suggests almost free variation on the part of the scribe, but in the Madrid Codex it seems that T162 WAJ HA’ is the standard or preferred order, 78 vs.11, and in the Paris Codex it is preferred 7 to 1. In all cases the order seems to have little or no bearing on the meaning, which is “food [and] water,” or more generally, “sustenance.”

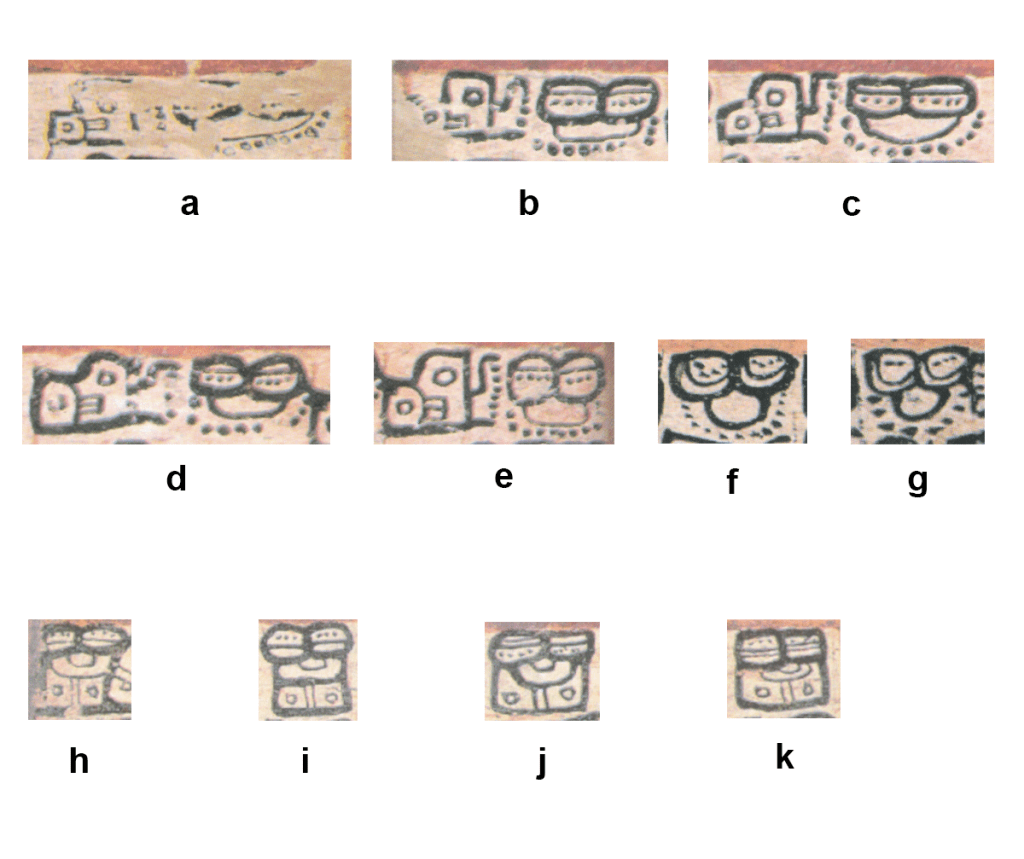

Variations in the appearance of the T162 superfix range widely, from the elaborate (D27a A3) to the barely recognizable (D67b F2) (Figure 7a, b). In the Madrid Codex, T162 has in some cases been reduced to little more than a pair of slightly elongated sideways U-shaped elements, e.g., Madrid Codex page 11c at C2 (Figure 7c). Importantly, it is also in the Madrid Codex that one finds examples of the T162 superfix that exhibit the same rectangular appearance, including horizontal lines of dots (Figure 7d-j), as the upper left-hand element of the subject of this note (Figure 1).

Taking the foregoing into consideration, it is our contention that the left-hand glyph of the collocation under consideration on D33a at B2, including the glyph superfixed to it (Figure 1), is graphically distinct from codical T604 K’UH/k’u and that the rectangular element over the cross-hatched oval is not part of the cross-hatched glyph at all but rather is the left-hand part of the two-part superfix T162 that is so ubiquitous in the codices.

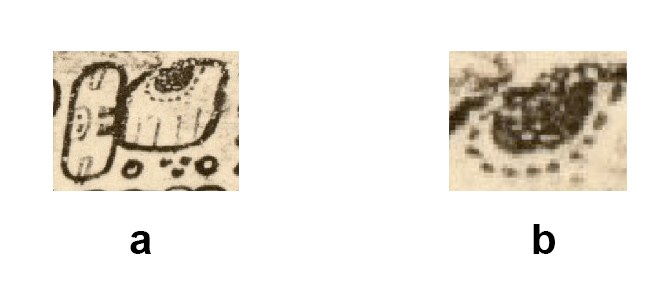

We propose that the cross-hatched glyph should be considered separate from the rectangular element seated above it, and that it is in fact a pars pro toto variant or allograph of the T501 HA’ logogram. Two examples of this logogram appear in separate contexts in the same almanac in D32a at H2 and D33a at B1 (Figure 8a, b). The HA’ logogram consists of a roughly rectangular enclosure with a darkened oval element at the inside top and a semi-circular arc of dots below it. Short vertical lines with hooked ends extend up from the inside bottom of the enclosure.

Graphically this image represents a water lily (Macri and Vail 2009:133) with the lines that extend from the bottom representing petals and the dark circle rimmed with dots representing the center of the flower (Stone and Zender 2011:172). In the Classic form of the HA’ logogram the darkness of the oval was represented by cross-hatching (ibid.), which was a standard form of symbolic representation for black in carved Maya art (Ibid.:120-121). There is one instance in which a T501 HA’ logogram in the Dresden Codex may exhibit the faintest vestiges of cross-hatching, on page 72a at E3 where it appears in the collocation CHAK HA’–la, chak ha’al, “great rain” (Figure 9a). The dark oval of the HA’ logogram, especially when magnified (Figure 9b), exhibits what seem to be small blank spaces consistent with cross-hatching, though admittedly such could just as easily be the result of coincidental damage.

Given the absence of elements characteristic of codical T604 K’UH/k’u (dual eggs and an enclosed area without cross-hatching) and the presence of elements specific to the T501 HA’ logogram (a darkened oval with cross-hatching and rimmed with dots), albeit minus the outline and the vertical lines representing petals, we suggest that the glyph in question is a pars pro toto variant of the HA’ logogram.

In addition to the graphic evidence just presented, there is also contextual support for reading the glyph in question as a variant of the HA’ logogram rather than as the glyph K’UH/k’u. As stated above, the T162 WAJ HA’ or T162 HA’ WAJ augury is one of the most ubiquitous across the codices, with 146 confirmable appearances (for examples see Figure 10). Throughout the Maya codices, the T162 superfix appears almost exclusively with the WAJ HA’ or HA’ WAJ augury, the single exception being on D72c at A1, where it appears superfixed to the T548 HAB logogram (Thompson 1962:161) (Figure 11). The presence of the T506 WAJ logogram to the right of the glyph in question, along with the near exclusivity of the T162 superfix being associated with the WAJ HA’ augury (and its variants), strongly suggests that the logogram in question, in the lower left below the T162 superfix, is in fact HA’ and is part of a HA’ WAJ augury.

Schele and Grube (1997:216) as well as Velásquez García (2017:61) did read the collocation that is the subject of this paper as an augury, “surplus of holy maize” and “nest? of food” respectively, but this paper has demonstrated that the augury in question is simply a variant form of the common T162 WAJ HA’ or T162 HA’ WAJ, and that the lower left-hand cross-hatched glyph is HA’. (Other variants of the common augury include T162 WAJ (preceded by a YAX logogram), T162 WAJ WAJ (three times), and T162 HA’ (Figure 12).

In this brief note, we have demonstrated that the glyph in question on D33a at B2 (Figure 1) is graphically distinguished from the codical T604 glyph K’UH/k’u and exhibits elements specific to the T501 logogram HA’ (a darkened oval with cross-hatching rimmed by dots). We have also demonstrated that the superfix to the collocation is T162, and that in the codices T162 appears almost exclusively with WAJ HA’ auguries. This inquiry provides ample evidence to support the contention that the glyph in question is not k’u or K’UH but rather is a pars pro toto variant or allograph of the T501 HA’ logogram.

Figures

Note: All images from the Dresden Codex are copied from the Förstemann facsimile generously made available online by FAMSI at http://www.famsi.org/mayawriting/codices/dresden.html. Images from the Madrid Codex are scanned from Matul and Fahsen 2007. Images from the Paris Codex are scanned from Anders 1968.

Bibliography

Anders, Ferdinand

1968 Codex Peresianus (Codex Paris). Introduction and commentary by Ferdinand Anders. Codices Selecti, Phototypice Impressi, Vol. IX [22-page boxed facsimile]. Akademische Druck- u. Verlagsanstalt, Graz, Austria.

Barrera Vasquez, Alfredo, Juan Ramon Bastarrachea Manzano, William Brito Sansores, Refugio Vermont Salas, David Dzul Gongora, and Domingo Dzul Poot

1980 Diccionario Maya Cordemex: Maya-Espanol, Espanol-Maya. Ediciones Cordemex, Merida, Mexico.

Kettunen, Harri and Christophe Helmke

2020 Introduction to Maya Hieroglyphs. https://www.mesoweb.com › resources › handbook › IMH2020

Macri, Martha J. and Matthew G. Looper

2003 The New Catalog of Maya Hieroglyphs, Volume One: The Classic Period Inscriptions. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, Oklahoma.

Macri, Martha J. and Gabrielle Vail

2009 The New Catalog of Maya Hieroglyphs, Volume two: The Codical Texts. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, Oklahoma.

Martínez, Hernandez, Juan

1929 Diccionario de Motul, Maya-Espanol, Atribuido a Fray Antonio de Ciudad Real. Merida, Mexico: Compania Tipografica Yucateca.

MacLeod, Barbara

1991 The Elusive T128. North Austin Hieroglyphic Hunches 4 (February 9)

Matul, Daniel and Federico Fahsen

2007 Códice de Madrid, Tz’ib rech Madrid, Codex Tro-Cortesianus. Reproduction with commentary by Daniel Matul y Federico Fahsen under the direction of Amanuense Editorial; printing and distribution by Nojib’sa Editorial y Litografía; published by Consejo Nacional de Educación Maya (CNEM), Guatemala City.

Schele, Linda and Nikolai Grube

1997 Notebook for the XXIst Maya Hieroglyphic Forum at Texas, March 8-9, 1997. University of Texas, Austin, Department of Art and Art History, the College of Fine Arts, and the Institute of Latin American Studies, Austin.

Stone, Andrea and Marc Zender

2011 Reading Maya Art: A Hieroglyphic Guide to Ancient Maya Painting and Sculpture. Thames and Hudson, London.

Thompson, J. Eric S.

1962 A Catalog of Maya Hieroglyphs. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, Oklahoma.

1972 A Commentary on the Dresden Codex: A Maya Hieroglyphic Book. American Philosophical Society, Philadelphia.

Velásquez García, Erik

2016 Códice de Dresde: Parte 1, Edición facsimilar. Arqueología Mexicana Edición Especial núm. 67.

2017 Códice de Dresde: Parte 2, Edición facsimilar. Arqueología Mexicana, Edición Especial núm. 72.

Suggested citation: Reichart, Clio and Uguku Usdi. “A Variant of the Codical T501 HA’ Logogram” Contributions to Mesoamerican Studies, May 27, 2023. https://brucelove.com/research/contribution-014/

Downloadable PDF: A Variant of the Codical T501 HA’ Logogram, by Clio Reichart and Uguku Usdi